Research hopes to understand interactions between intestine and liver

block

According to National Institutes of Health research, the gut-liver axis is the relationship between the gut, its microbiota, and the liver, resulting from integrating signals generated by dietary, genetic, and environmental factors.

There is still much unknown about the human gut-liver models, so Richard and Loan Hill Department of Biomedical Engineering Professor Salman Khetani is creating models to understand the interactions between the intestine, liver, and microbiota. Khetani aims to develop a scalable, primary cell-based human gut-liver model for compound screening and disease modeling applications.

Along with Nancy Allbritton of the University of Washington, Khetani received an NIH R21 grant to create an intestinal liver model to understand how the liver and intestine affect each other in the body and study how each of the tissue types regulates each other’s functions in its early and conceptual stages.

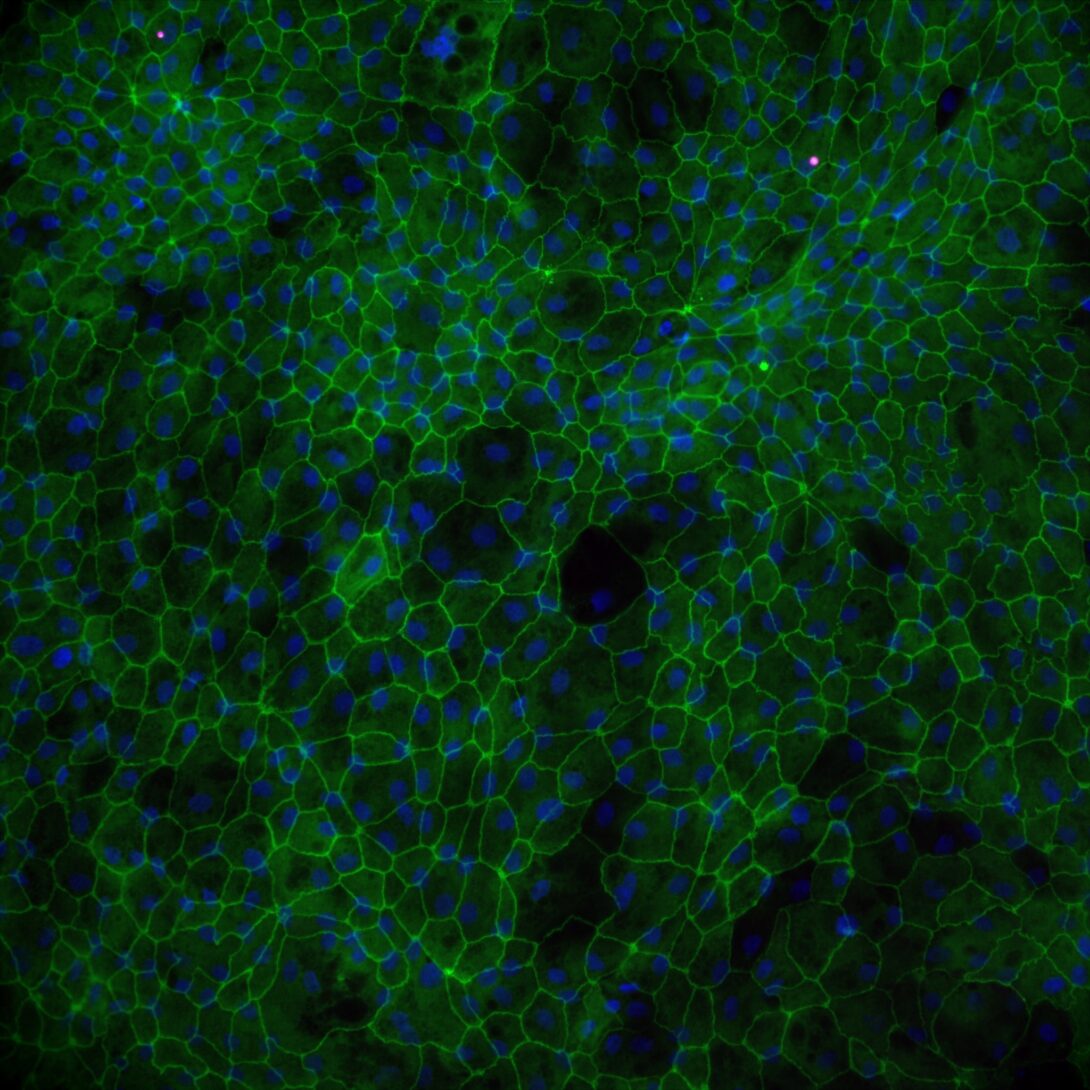

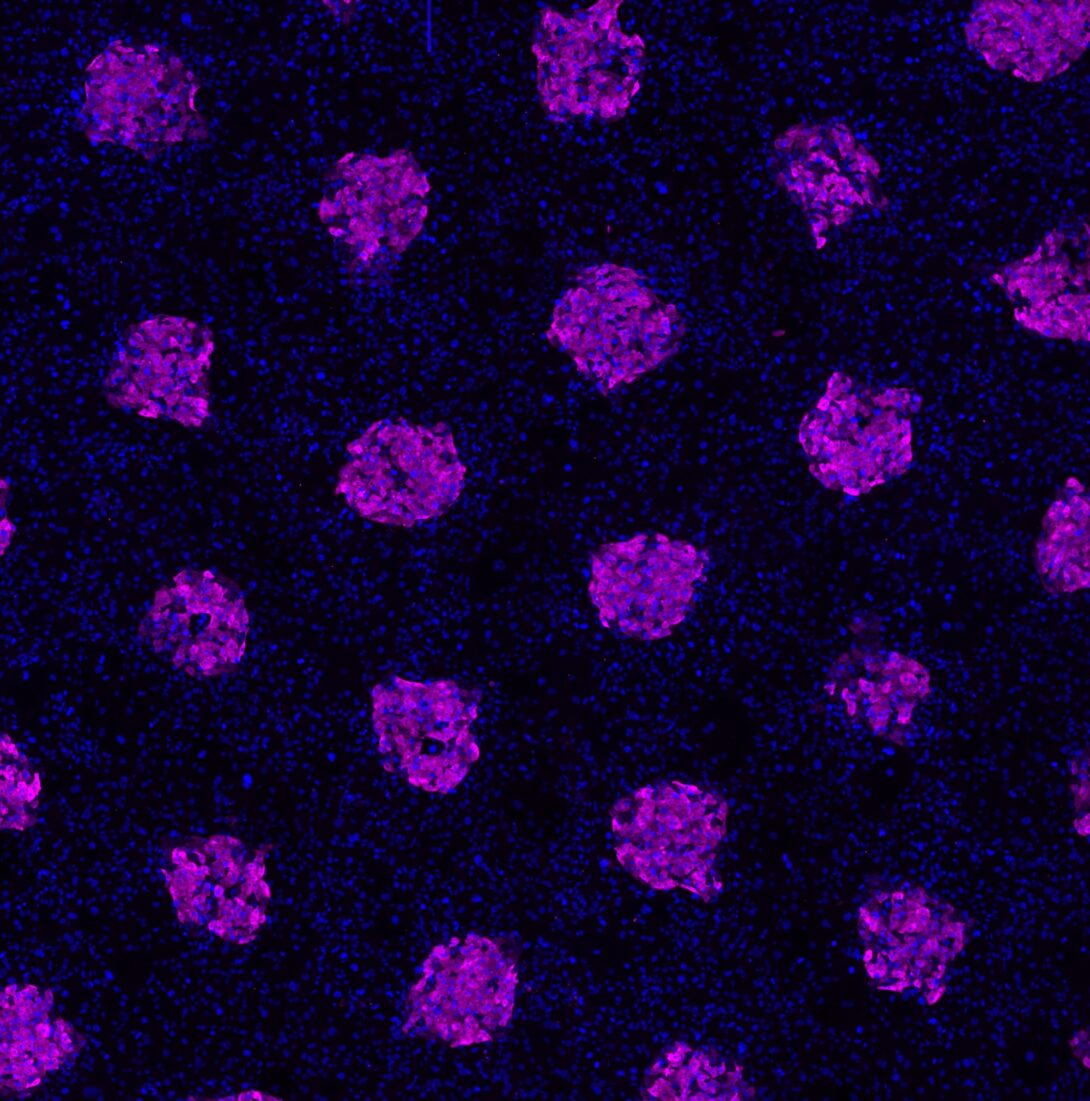

Their research involves putting liver cell droplets at the bottom of the wells and the intestinal cells from patients on the top.

Using these intestinal cells from Allbritton’s lab, they will be putting bacteria into the intestinal compartment, and within a person’s microbiome, there are a lot of bacteria in the intestines.

“We have found that the liver boosts intestinal functions, which was surprising to us because they’re connected by blood supply, but that they can boost intestinal functions is interesting,” Khetani said. “Our research of intestinal metabolism of drugs is in early stages, but we are interested in understanding how drug absorption and metabolism by the intestine is processed by the liver.”

He noted one boosts the function of the other to facilitate the metabolism absorption of drugs, meaning they are correctly absorbed and eliminated from the body once they’ve done their job.

“I think we’re going to discover some exciting things about how they’re talking to each other in a physiological way,” Khetani said.

block

An R21 grant is a high-risk, high-reward grant, and there is no previous data to suggest that this could work, but the idea is that there are two years for research on this concept. Khetani explained that if this research is successful, it could be a useful tool for understanding the mechanism for screening drugs.

Khetani is interested in three diseases: acute liver injury, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and alcoholic liver disease (ALD). So, an intestinal-liver model can apply to all three because the result of the diseases is essentially that gut health is being ruined, and with the microbiota and microbiome playing a role, it’s been implicated in all three ailments.

“We hope that as we build this model, we will be the applying for additional grants where we’re studying NAFLD, ALD, and drug toxicity from the perspective of a multi-organ interaction and not just the liver,” he said.

Currently, when drug tests involving the liver, the drugs are put directly on the liver despite that this is not how it happens through the body.

Khetani also noted that this would be the first model with all human primary cells, which come from patients who have passed away. They’re specifically going to study the biology of the interactions between these cells and develop technology around them. He and his team hope that in the future, it could be used for drug screenings or disease modeling.

“We hope that in the future, we’ll be able to study these diseases and drugs, so it should have far-reaching implications for our research and many other researchers,” he said. “We are so focused on researching the disease that we forget we still don’t know much about how the body works.”

PhD student Dinithi Samarasekera is assisting with the gut-liver R21 research.

Salman now has four R01, three R21, and two NSF active grants as Principal Investigator or Multiple Principal Investigator and is on two additional R01 grants as Co-Investigator.